1.1 An Introduction to You Are Ruining Me

If you’ve seen Titicut Follies, Frederick Wiseman’s 1967 documentary about Bridgewater State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, chances are you remember Vladimir, an articulate young man with an odd accent and a friendly demeanor. Vladimir was my uncle, and this is my serialized memoir about him.

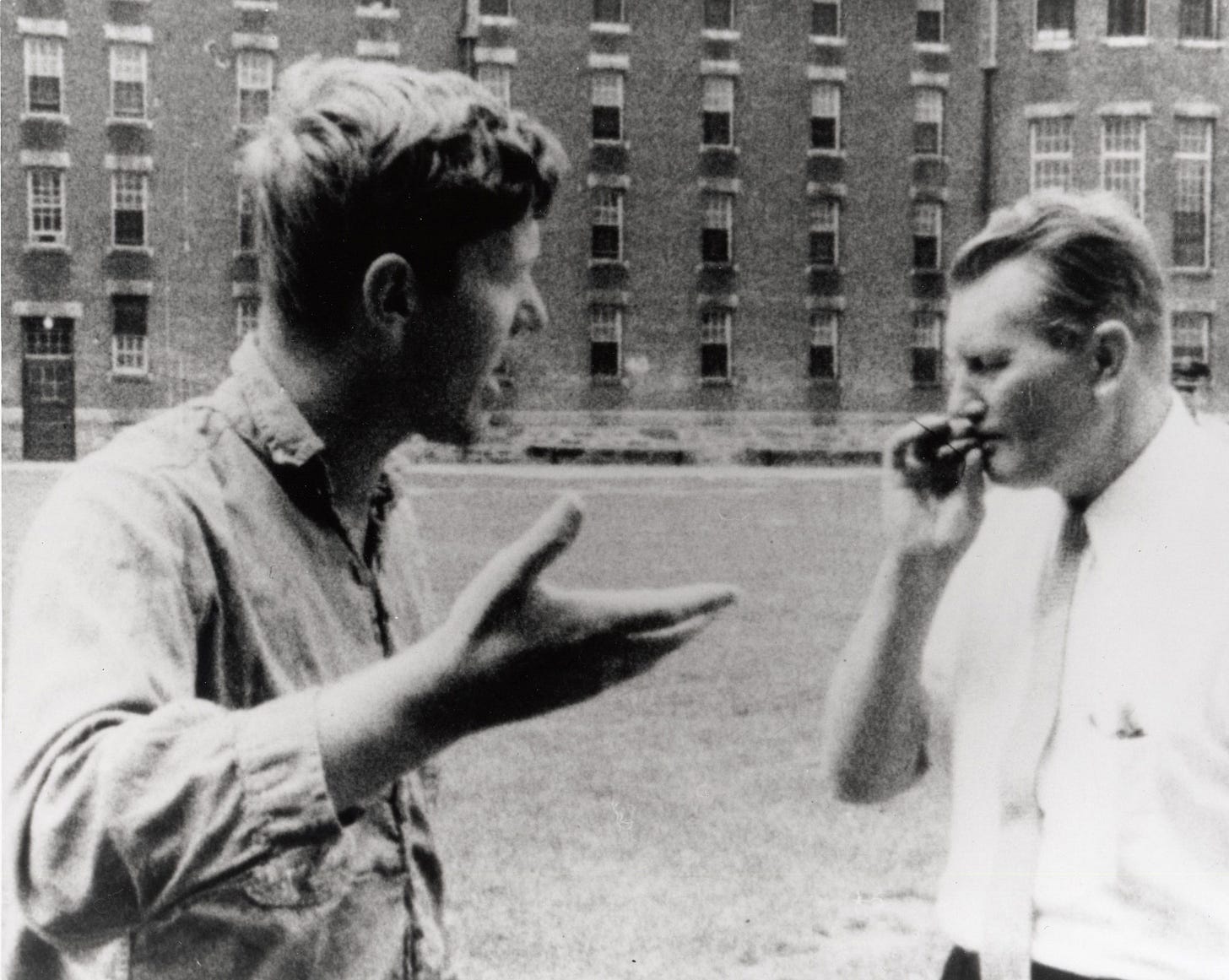

Here is a compilation of scenes from the film, to refresh your memory or introduce you to it, as the case may be, including the scene in which Vladimir says the line from which the title of my work is drawn: “You are ruining me.” His fear of what is happening to him is palpable, and warranted, I think.

Vladimir’s quest to convince his doctors that he was sane enough to leave Bridgewater, and return to the regular prison population at Walpole, from whence he came, forms something of a narrative arc in the documentary. In an interview, Wiseman said Vladimir’s story was the film’s “fulcrum”: that his “critiques of Bridgewater are quite reasonable, but it’s also true that he needed help, because he thought his coffee was being poisoned.”1 I think it’s this complexity, and what seems Vladimir’s genuine good nature, despite the bedlam around him, that rouses sympathy and pity, making a seemingly indelible impression on viewers of the film.

It’s how I understand, anyway, the fact that nearly every time I read about Titicut Follies, I find interesting comments about, or ruminations on, Vladimir — whether it’s in scholarly articles, magazine or newspaper stories, on blogs, on YouTube clips, or on social media. A garage band even wrote a song about him, though they made up details and of course got it all wrong. In fact, because there is virtually no public information about Vladimir, almost everything I find written about him is wrong. There are partial truths, in spots, but those are garbled, at best.

But if my purpose were only to relay the simple facts of Vladimir’s life — when and where he was born, his turns as war refugee, immigrant, inmate — I wouldn’t need a memoir to do it, a Wikipedia entry might do. I have spent many years, decades now, researching and writing this story because in the same way that Vladimir was the fulcrum of Titicut Follies, he was the fulcrum of his refugee family. His Russian father and Ukrainian mother persevered through the horrors of the first half of the Russian twentieth century — world wars, revolutions, civil war, famine, collectivization — and brought their four children to the United States in 1951. They had no naïve belief in an American dream, at least not for themselves, but they hoped, as all parents do, for a better life for their kids, and none more than their first-born son, Vladimir. That hope was shattered only a few years after they arrived.

I grew up amidst those shattered hopes, though I didn’t understand that then. Vladimir was the central mystery of my childhood. I knew him through old photos in an album, the whisper of his name by a relative, a letter from him every now and then — bafflingly addressed to me as “Goddess” and my brother as “God” — and once or twice a year, as a funny, high-pitched voice on the telephone, asking me the usual awkward adult questions about school and what Santa Claus brought me. I knew too that he was the source of the desperation I sometimes heard in my mom’s voice, when she was on the phone with some official or another, the same way I understood that the arguments in Russian between my mom and my grandmother, or between my mom and her brother and sister, had him at the center. But I didn’t learn, in a straightforward and simple way, where exactly he was and what exactly he had done, until I was thirteen. And, as is often the case, at least for me, that first bit of solid information only raised more questions.

This memoir is the result of my need to understand what happened to him, and the whole family, which propelled me on a lifetime of study. I majored in Russian history in college and started a PhD program in Russian history too, though I did not finish. I spent a summer in Russia. Vladimir became a friend and companion on this journey, answering endless questions about his childhood, Russia, and German DP camps. He had a remarkable memory. I phoned him once, from a small town in Russia where I was doing genealogical research, and he called up a thirty-year-old memory of an address for me! Late in his life, he became again a kind of family fulcrum, a virtual switchboard back when it cost real money to make long distance phone calls, as he regularly kept in touch with his nieces and nephews and kept of us informed of each other’s doings as we set out on our adult lives. He was a kind and intelligent man, one of the cheerleaders of my life, and I still regularly wonder what he would make of this or that, and no more so than in the last year.

Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has prompted me into the past, once again, back through family memories and immigrant lore. Especially, I’ve looked more deeply at western Ukraine, where my grandmother was born in 1912. She was a difficult woman, at best, practically unknowable, a figure both malign and nearly featureless in my memory. My feelings about her are so complicated that they formed, I see now, a real stumbling block in putting this story together. But thanks to some new (or newly discovered by me) history books, online sources, and online communities of descendants of the region, I finally have some landmarks to navigate by. And, as for so many, following the war closely online has generated enormous empathy for what Ukrainians are going through, which helped me in turn to find, finally, the kind of empathy for my grandmother that is necessary for writing memoir.

Marc Mohan, “Frederick Wiseman talks ‘Titicut Follies,’” Oregon Arts Watch, April 18, 2016, https://archive.orartswatch.org/frederick-wiseman-talks-titicut-follies/.